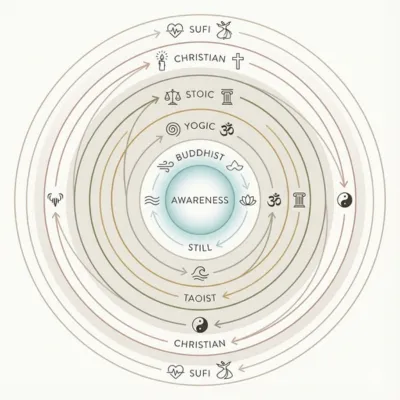

Presence practices across traditions

Across cultures and eras, presence has been trained in remarkably similar ways. Different languages, symbols, and rituals, but the same core aim: stabilize attention, reduce reactivity, and anchor awareness in direct experience rather than narrative.

Shared foundation

Presence is not trance or withdrawal. It is heightened contact with what is happening now.

The body is the primary anchor. Breath, posture, sensation, and movement are used to interrupt mental drift.

Repetition matters. These are practices, not insights.

Stoic

Attention to impressions before judgment.

Frequent self-checks: What am I reacting to? What is actually in my control?

Presence as readiness. Staying inwardly composed while engaged with the world.

Buddhist

Mindfulness of breath, body, feelings, and mind states.

Observing without grasping or resisting.

Presence as clear seeing, moment to moment, without identification.

Yogic

Breath control and sensory withdrawal to steady awareness.

Yoga Nidra and meditation to maintain awareness through changing states.

Presence as continuity of awareness, even as the mind quiets.

Taoist

Soft attention rather than effortful focus.

Sensing alignment with natural rhythms.

Presence as responsiveness without forcing.

Christian contemplative

Centering prayer and silent watchfulness.

Releasing discursive thought to rest attention.

Presence as attentive openness rather than analysis.

Sufi

Remembrance practices using rhythm, breath, or phrase.

Presence as recollection of what is most real, here and now.

What unites them

Less thinking, more noticing.

Training the gap between stimulus and response.

Returning again and again to direct experience.

Presence is not a belief. It is a trained capacity.

Traditions differ in style, but the skill being developed is the same.